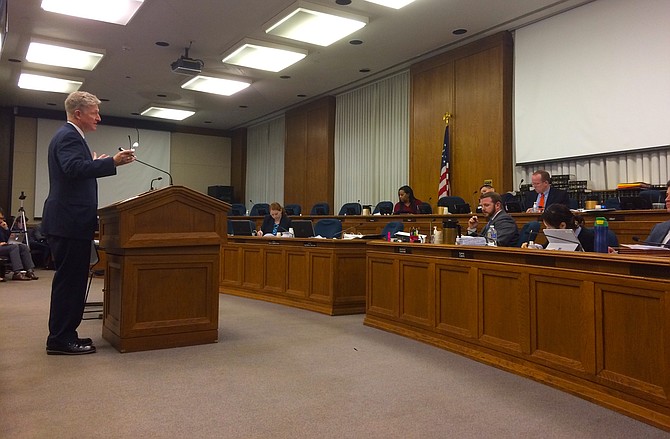

Secretary of Public Safety and Homeland Security Brian Moran tells lawmakers to balance their concerns about the cost of not penalizing people with the cost of filling up Virginia jails for no reason. Photo by Michael Lee Pope.

When Ryan Johnson was in college at Virginia Tech, he made a stupid decision. He got high with a group friends, and he got caught. The police charged him with less than a gram of of marijuana. He was an honor student, and he was the first in his family to go to college. But suddenly he found himself caught up in the criminal justice system.

One part of his sentence puzzled him, though. It wasn’t the monthly visits with the probation officer or the random drug tests. It wasn’t the drug and alcohol education program or the the community service at a nursing home. And he paid all the court fines while working a part time job at night after school. What surprised him was the loss of his driver’s license.

“I though to myself how why is my license being suspended for something that didn’t involve a car or driving?” he explained to lawmakers during a hearing this week. “How am I supposed to get to school or work? How can I pay for my fines and my court costs and my lawyer if I can’t get to work?”

Johnson is not alone. About 200,000 people in Virginia have a suspended license for a legal infraction that has nothing to do with a driving offense. Virginia is one of 15 states that impose mandatory driver's license suspensions on simple possession charges that do not involve motor vehicles. And 650,000 people in Virginia have a suspended license for failing to pay court costs, mainly drug offenses and child-support violations. Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe told lawmakers earlier this month he wanted to make the issue of restoring drivers licenses to these people one of the hallmarks of this year’s legislative session.

“Another step we can take to protect Virginians’ economic productivity is to limit the number of people whose driver’s licenses are suspended due to unpaid court costs and non-driving related offenses,” said McAuliffe. “Suspending people’s driver’s licenses limit their ability to work, which only makes it more difficult to earn the money to pay off their debt and build better lives.”

REPUBLICANS AGREE with McAuliffe that too many people suffer from suspended drivers licenses, and leaders in both parties met this week in a House committee room to forge a compromise, sifting through about a dozen legislative proposals to craft a set of proposals with bipartisan support that is likely to be one of the major accomplishments of the 2017 session.

“Many of them are driving now, and then they get stopped and they get arrested for driving on a suspended license,” said Brian Moran, Secretary of Public Safety and Homeland Security. “I would just ask you to balance your concern about the cost of not penalizing that person with the cost of their being arrested for driving on a suspended license and filling up our jails.”

According to the version of the legislation that emerged from a House Courts of Justice subcommittee this week, those who are convicted of a non-driving related offense would be able to serve more community service instead of having their driver’s license suspended. The amount would double from 25 hours to 50 hours. And, as one delegate noted, many times community service is very difficult and grueling work.

“At first they’ll say they want to be on litter duty instead of being in the jail” said Del. Ben Cline (R-24). “And after a few eight-hour days of picking up litter in 95-degree weather, they want to go back to jail.”

Delegates struggled with the best way to handle those who have not paid court costs and fees. Their major concern was finding a way to keep people from gaming the system, evading local court clerks and potentially clogging dockets with unnecessary hearings and appeals. One of the problems is that many court clerks demand a 50 percent downpayment on court costs, which many people are unable to pay. Ultimately, they were able to create a deferred payment system that has unanimous support from Democrats and Republicans.

“If people are going to pay, they’re going to pay,” said Martin Kumer, superintendent of the Albemarle jail. "And they certainly won’t pay if they don’t have a job, and they can’t drive to and from their job.”